Sunspots and Star Spots

During an approximately six-month period from October to April, the massive bright star Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion the Hunter dropped by 40% in brightness. Astronomers were perplexed and amateur astronomers were awe struck by the affect the change had on the familiar appearance of the familiar winter constellation. Up all night during the season, it was a reminder that something very unusual was afoot, but what was causing it?

One of the initial leading theories was that the dimming was caused by an opaque gas or dust cloud orbiting or ejected by Betelgeuse. A rather dense region of the stuff passed between us and the star and caused the star’s brightness to diminish. Think of the way a cloud passing in front of the sun on a clear day dims its light.

Another plausible theory has gained acceptance among astronomers at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Astronomy this summer. According to it, large dark “star spots” on the surface of Betelgeuse rotated around to its side facing Earth. The spot or spots were so large that they reduced the effective radiance of the star in our direction.

Betelgeuse was already known to vary in its brightness, putting it in a class known as “variable stars. There are numerous conditions and circumstances that may cause a star to be a variable, one of which is star spots. Stars whose brightness changes are due to spots are said to be non-periodic because the occurrence of spots is unpredictable.

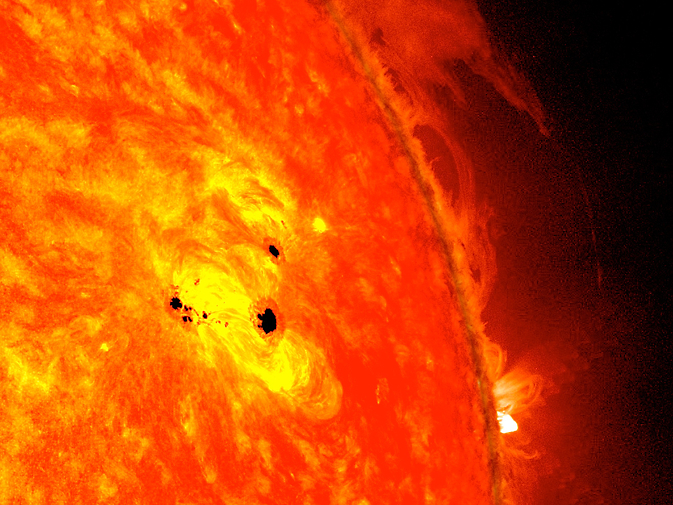

Our star, the sun, also has its own star spots, but we call them sunspots. Sunspots are relatively small even during sunspot maximum during the 11 year “solar cycle.” A typical sunspot has a diameter about the same as planet Earth, or roughly a little more than one percent of the solar diameter.

Betelgeuse is a red giant star about 500-700 light-years away with a mass 10-20 times that of the sun. It is also extremely large. So large that if it replaced our sun, the orbital paths of the four innermost planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars) would be enclosed within the star. Astronomers estimate that a star spot would have to cover 50%-70% of the visible surface of Betelgeuse in order to cause the observed dimming effect. Such a spot or spot complex would be truly gigantic.

Our own star’s sunspots have dwindled during the past several years. A new cycle has just begun and, like the previous one, is expected to be “weak” according to astronomers. When amateur astronomers get together it’s common to hear someone report observing a rare Aurora Borealis (northern lights). Now days, frequently one will hear about the sunspot that someone recently saw through their properly and safely filtered telescope.

As far as Betelgeuse goes, additional observations over time will confirm whether the star spot theory of the star’s dimming will be supported.

–Curt Roelle